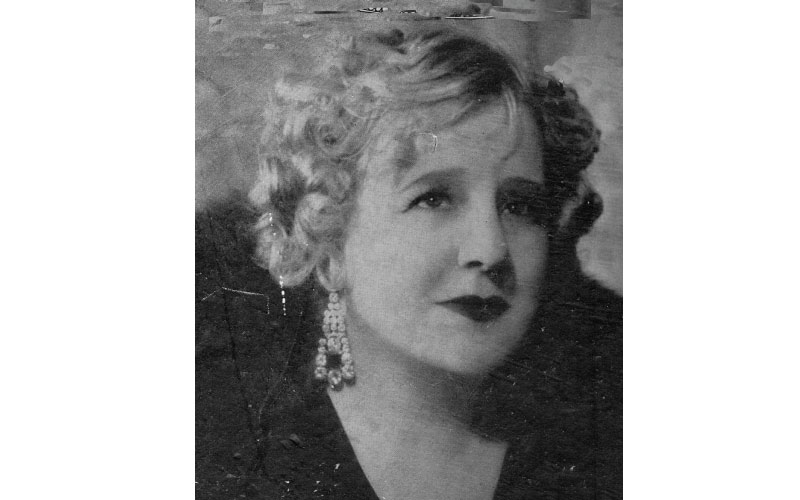

Violet Van der Elst (1882-1966)

A WASHER-woman and a coal-porter’s daughter, Violet Van der Elst saved both the condemned from the gallows and Harlaxton Manor from demolition.

She rescued the 1830s building when she bought it for £90,000 in October 1937, after seeing an advertisement in Country Life. It had become derelict and faced being reduced to rubble without a wealthy new owner. It had been rumoured that the Duke of Windsor had tried to acquire it, while his Grandfather, Edward V11, had also tried to buy it as a summer palace, but after failing, bought Sandringham instead.

She renamed it Grantham Castle and restored the interior, filling it with antique furniture from Buckingham Palace and Rufford Abbey, adding the large marble fireplace in the front entrance hall, and the Great Hall’s crystal chandelier which she claimed was the largest in the world.

Violet banned shooting on the 427-acre estate, despite a passion for wearing Russian sables, and opened it to the public.

She collected books on the occult and hid money under carpets to test her maids’ honesty.

In 1948 she returned to Surrey, where she was born Violet Dodge, after selling the house the Jesuits for a mere £70,000. It is now the University of Evansville campus.

Mrs Van der Elst had become disillusioned with the Manor after it was requisitioned for the war effort, when the War Agricultural Committee ploughed up 100 hectares of parkland.

She said: “I felt part of me was taken away.”

She had based the Women’s Peace Legion at Grantham Castle, and took out advertisements in national papers claiming women could end war for all time.

Violet was 17-years-old when she married engineer Henry Nathan, who died in 1927.

After working as a scullery maid and a brief stage career, she made cosmetics in her kitchen, before making a fortune by developing Shavex – the first brushless shaving cream.

In 1934 her second husband, Jean Julien Romain Van der Elst, a Belgian (whom she married just four months after Henry’s death), died suddenly. In his memory she dedicated her life to the abolition of capital punishment. She kept his ashes in an urn on the ledge of a stained-glass window in the Great Hall at the manor.

The following year, she sacked her aristocratic secretary Lord Edward Montagu for embezzlement, a man who three year’s earlier had been arrested (and released) in the USA for murder.

She replaced him with 19-year-old New Zealander Ray Winston, whom she sacked and reinstated almost daily. A connecting secret passage has since been discovered between their respective bedrooms.

She claimed to be a direct descendant of Elizabethan seadog Sir Guy Goundry, who was killed raiding Cadiz, in Spain.

And she was a prolific composer, publishing (through her own company) more than 200 pieces, despite being unable to read or write a note of music. She employed professional musicians to do that.

She spent much of the Second World War at her Kensington home, as the military took over Harlaxton Manor. There she showed extreme bravery, putting out incendiary bombs with buckets of water and driving through a blitz toi deliver blankets to the needy.

A quarter of a century of campaigning saw Mrs Van der Elst outside prisons across the country nearly every time an execution took place.

An imposing figure, weighing 15 stone and always dressed in black, her highly visual and well organised protests saw planes trailing black flags and hordes of sandwich-men on the ground, all accompanied by a brass band playing the Dead March in Saul.

Violet set up her own newspaper called Humanity, published evidence she believed proved condemned people were innocent, and wrote other campaigning pieces such as The Torture Chamber and On the Gallows.

Although she failed to enter Parliament as an MP on three occasions, she is commonly regarded as the person who did most towards the abolition of capital punishment in Britain.

Almost broke, she she moved to Knightsbridge in 1959.

Sylvia Dearing adds that when Violet Van der Elst sold her house in Kensington in 1959 it was to a John Menasee, He rented out the house in Addison Gardens, Kensington and was made aware of this by a friend of his. I lived in the Addison Gardens property with my ex-husband until 1961.

Whilst living there we found something of interest which we were surprised that Mrs Van der Elst would leave behind.. It was a marble casket with two compartments, one of which had the remains of Mr Van der Elst, which were not ashes but bones which appeared to be cremated.

I am pleased that there were people, with a conscience, such as Violet Van der Elst and that the death penalty was eventually abolished in this country

In 1965 Mrs Van der Elst saw her tireless protesting rewarded when the death penalty was abolished.

However, despite her achievement she died the following year destitute and alone, having spent her fortune campaigning.

As she once told a Picture Post reporter: “I have made three fortunes and lost five.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.